A Blessing in the TreesA short story by Phillip C. Landmeier“Come on Daddy. Hurry up.” said my five year-old daughter, as she trotted up the path. “O.K. I’m going as fast as I can. Hey, wait a minute, Athena. I want to have a look at these palapas.” I called out. Each palapa was a round building, about 25 feet in diameter, with a roof made from the leaves of a particular palm tree called “manaca”. “Come on Daddy. We have to hurry. The biotopo closes at 4:30.” “Yes, I know, but I want to have a look here.” We really did have to hurry if we were going to finish the long hike in time, but I had already decided we probably weren’t going to make it. I looked up at our goal, a waterfall 1,200 feet above us, and shook my head. I had seen this waterfall once before, but only a glimpse, through the stained and scratched window of a bus as we careened around a curve in the two-lane mountain road that passes by. On that day, even though it was late afternoon, the mountain was still shrouded in cloud and mist. I barely saw a hint of the waterfall at the top. Today, the mists and cloud had risen during the morning and the view was crystal clear. Far in the distance, the water seemed to be falling in slow motion and I realized the waterfall was much taller than I had thought. Since the waterfall was only a small feature at the top of the mountain, the magnitude of the climb became clear. My heart sank. I am not the hiker-type who does this sort of thing for fun. Even so, I was determined to see the wonders of this cloud forest that I had read about. I figured there was no way our little group consisting of my wife, April, my 15 year-old son, Phillip, and especially my five year-old daughter, Athena, was going to make a steep climb and descent through tropical rainforest in four hours. I doubted whether even I could do it. Athena came running back and poked her head through the door of the first palapa. Fastened to the outside of the first palapa was a large map entitled: “Biotopo del Quetzal”. In English we would call it a wildlife preserve, but the sense of the word “biotopo”, in Spanish, is more like a place where one can go to encounter wildlife. We were here to see the cloud forest but we also hoped to see some quetzals, a rare and elusive tropical bird found only in the handful of true cloud forests remaining in Central America. The quetzal (Pharomacrus mocino) is of the genus Pharomacrus of the trogon family. Also called the resplendent trogon, the odd-looking quetzal is a large bird, 9 to 18 inches tall, iridescent green overall with a blood-red breast. Its 3 foot long tail brings the overall length of the quetzal to 50 inches (125 cm). The quetzal’s head is crowned with a puff of spiky feathers--its head looks like a giant milkweed flower. “Quetzal” is a Nahuatl word meaning “beautiful feather”. This word also occurs as part of the name of the Aztec god, Quetzalcoatl, which means “beautiful feathered serpent”. The jaguar, along with the quetzal, are especially revered in Mayan mythology. According to ancient Mayan law, killing either of these animals was punished by death. Only the king was allowed to wear quetzal feathers. Part of the charm of the quetzal is its ridiculous appearance. Mayan tradition demands respect for the quetzal but their mythology also recognizes and explains the bird’s bizarre plumage. According to the creation myth recounted in a long narrative called the Popol Nuh, the quetzal originally had no feathers but was blessed with a clever mind and a persuasive voice. The quetzal convinced several other birds to give him parts of their plumage so he would not be naked. Thus, the quetzal looks like a patchwork of incongruent parts. The myth goes on to tell of how the quetzal, sneaky con-artist that he is, used his striking appearance, his clever mind, and smooth talk to become the king of all the birds. Later, he ridicules and betrays the birds who took pity on him and helped him to become great. Finally, his pride and abusive behavior offend the gods and he is stripped of his ability to speak. He loses his high position and becomes a recluse. Despite the best efforts of biologists, quetzals refuse to live in captivity, much less reproduce in captivity. This rare species ranges over a large area every day and, if caged, always dies within a few days. The only way to see one close-up is stuffed in a museum. The quetzal is, therefore, a symbol of liberty. It is the national bird and the name of the currency of Guatemala. April joined me at the map and asked, “What do you think?” “Well, the main path goes all the way to the top, to the waterfall, and back down to the highway here--five kilometers, about three miles, and an elevation change of 2,400 feet. There’s a shortcut here,” I said, pointing with my finger, “that goes about halfway up, cuts through the lower part of the cloud forest, and knocks off about two kilometers. I don’t know. I can’t imagine Athena making it. I have no idea what’s up there. I’ve got my rock-climbing boots on but she just has tennis shoes. I don’t know...” “I think she can do it.” said April. “All right. We can wait to make a final decision here,” I said, pointing to the fork in the path, “and I can carry Athena if she runs out of steam.” We made a quick inspection of the empty palapas. There wasn’t a soul around and it was completely silent except for the occasional rumbling of trucks on the nearby highway. “Who lives here Daddy?” asked Athena. “Nobody.” I said, “These are all-purpose shelters for students or scientists making field trips here to study. They can sleep here, set up laboratories, or whatever.” “C’mon Dad,” called my 15 year-old son, Phillip, from some distance outside the palapa, “I’m hungry!” Fifteen year-olds are always hungry and he knew that April would not allow a food break until we had made some progress on our journey. I doubt he was much interested in the natural wonders before us but the sooner we got up that mountain, the sooner he could eat. “We’re coming.” I shouted as we left the palapa and turned right, up the trail. Athena took off running to catch up with her mother. I settled into a steady stride and shifted mental gears to become consciously aware of my environment, scanning every detail with my eyes, listening, smelling, and hoping to learn something. The path was good, rising gradually, and we soon caught up at the base of some stairs cut directly into the soil and held in place by vertical wooden boards supported by stakes driven into the ground. The path was consistent: gently rising stretches interrupted by short flights of steps. “Someone’s done a lot of work here.” I said. “Yes. Neat way to make the path easy for people without messing up the environment.” said April. Presently, we came upon the fork we had seen on the map. We could turn right and cut across the face of the mountain or take the left-hand path to the top. “I’m hungry. Let’s eat.” said Phillip. “Phillip, you have a one-track mind.” said April. “It’s not my fault that I’m hungry. I haven’t eaten since breakfast.” “Yeah, all of two hours ago.” I said. “I’m thirsty.” said Athena. “All right.” I said, feeling outnumbered, “It’s now exactly noon and this might be the last comfortable spot we’ll find.” Alongside the fork in the path were some log benches with a manaca roof overhead--a rest stop. “I guess they put this here for people like us who can’t decide which way to go. Let’s eat and then decide.” I said. Always looking for the bright side, I added, “Besides, we’ll have that much less to lug to the top.” We unslung our packs and dug out the goodies we had brought along. The señora at the family-run place where we spent the night had prepared our lunch: homemade tamales wrapped in banana leaves, roast chicken, and tortillas. There’s nothing more delicious than country food and, for me, there’s comfort in knowing the exact origin of what I’m eating. The chicken we ate for lunched squawked its last squawk this morning while we ate breakfast. The tortillas were wrapped in hand-woven Mayan cloths; They were steaming hot and had that unique smokey flavor of Guatemalan tortillas, acquired as they roast on the comal over an open fire. These were made by the señora’ s daughter in the same way that Q’ek’chi Mayan women have made tortillas for thousands of years--clapping the corn masa between their palms: pop clap clap, pop clap clap... Just thinking about it makes me hungry. Finishing the last of my lunch, I strolled to the edge of the clearing we were in to get another look at our goal. The waterfall was still far above us, nestled in a gray granite outcrop. Looking to the east, away from the waterfall, I could see down two valleys, one stretching to the east, and one to the northeast. We were in mountainous country, about 4,000 feet above sea level, at an elevation where the type of vegetation changed. Below us were tall, dense pines reaching 150 feet in height. In the distance I saw occasional steep slopes that exposed the rich red color of the local soil. Above our elevation, the pine trees gave way to a mixture of many kinds of lower trees and bushes. “April, come have a look at this.” I called. “Notice how the vegetation suddenly changes at this elevation”. “Wow. What a pretty view. Look at the color of some of those pine trees. You should take pictures.” “I will. Those flourescent green colored trees don’t look natural. I didn’t know that kind of color occurred in nature. I could spend the whole afternoon right here.” “Daddy! You said we were going to the waterfall.” said Athena, between sips from a can of soda. “That’s true Athena. I was just kidding.” I said. “We’re going right now as soon as we clean up our trash.” “It’s already done.” said April. “Let’s go.” Our decision was made and we marched up the left-hand trail without further discussion. The trail plunged directly into deep shade and we found ourselves in a different world: a rainforest. It was not what I expected. I’m not quite sure what I expected--perhaps a jungle of dense vegetation, hanging liana vines, chattering monkeys, screeching birds, slithering snakes? The rainforest was none of these things. “It’s not as dark in here as I thought.” said April. “No. Our eyes just have to adjust from the bright noonday sun.” I replied. “Look at the size of some of those trees. They must be very old.” “I don’t know. I read about trees like this. They have buttresses around their bases to support them better in wet soil.” The trees we were looking at had smooth gray bark and smooth tall trunks with few branches. Near their tops, about 50 feet above us, they sprouted dense branches and leaves up in the sunlight to form the canopy of the rainforest. The canopy was so dense it let through almost no direct sunlight. Here and there, a shaft of sunlight stabbed through, spotlighting a tiny patch on the forest floor.

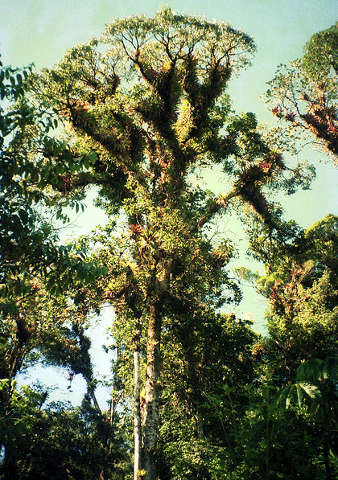

Photo taken during the hike--an example of one of the types of rainforest in the biotopo. Between the floor and the canopy was mainly empty space and we could see a long way in all directions. “It’s almost like this forest is upside down compared to the pine forest we just came from.” I said. “What do you mean?” asked Phillip. “Well, the pine trees are thick at the bottom and thin at the top. Near ground level it is very dense and you can’t see far at all. In here, the trees are bare until you get way up to the canopy. All their leaves are at the top.” I replied. We could have seen even farther if the ground had been flatter. The forest floor was covered with many kinds of plants. Most were low shrubs about a foot tall and there were some ground-hugging vines. The tallest plants on the ground were no more than 3 feet tall. The plants on the ground seemed to maintain a polite separation without getting tangled--possibly to make the most of what little light filtered down from the canopy above. “Hey. What’s that?” asked Phillip, pointing to a yellow and orange growth sticking out of the side of a tree just off the path. “Looks like a fungus or some kind of mushroom, Phillip.” I replied. We left the hard-packed dirt path and walked on the spongy dark brown earth between the plants to the tree. The fungus looked like half of a large serving platter with scalloped edges, reminiscent of a giant sea clam. It was colored yellow and orange and was coated with a clear sticky substance. “Interesting huh? I think the Chinese eat mushrooms much like this one.” I said to Phillip. “I’ll pass.” “Oh c’mon Phillip. We eat Chinese food all the time. I’ll bet we’ve already eaten something like it without even knowing it.” “Yecch!” “Why are we whispering? Have you noticed how quiet it is in here? It’s dead silent. It’s so quiet I can hear my own heartbeat.” I noted. “It’s weird.” “Yeah it is, but I like it.” “We’d better go chase after Mom and Athena.” said Phillip. The path ahead lay almost straight except for a few shallow dips. The whole path was visible for a long way and it was empty. “They really got ahead of us. We’d better step on it.” I said as we strode off quickly. It was so quiet I could hear the whoosh of the wind in my ears caused by our walking. I paused a moment, cupped my hands to my mouth, and shouted, “April!” The sound of my loud voice seemed to die a few feet in front of me. I resumed my fast walk and commented, “The acoustics are really strange in here. It’s like being in a soundproofed room... must be all the organic material here absorbs sound.” “Spooky.” said Phillip and shouted, “Mom!” Silence. “Well, they have to be up there somewhere. You can’t exactly get lost on this path and we can walk way faster than they can.” At our fast pace, we soon reached the point where the trail previously disappeared. It made a half-right turn through some denser vegetation and another straight segment lay before us. As soon as we passed the turn, we saw them both, about 100 feet ahead, stooping down examining a plant. “Hey, didn’t you hear us?” shouted Phillip. “No. We didn’t hear a thing. We knew you slowpokes would eventually catch up to us.” replied April. “Are you sure you didn’t hear us?” I asked. “Nope. Didn’t hear a thing.” “I can’t believe that. We both called and you should easily have heard us. The acoustics in this rainforest are really strange.” “What are you looking at?” asked Phillip.

The strange bromeliad. “A bromeliad.” replied April. “Isn’t it pretty?” The plant looked like a miniature century plant with a single stalk growing straight up in the center, topped by a pinecone-shaped red flower. “I thought bromeliads grew on tree limbs.” said Phillip. “Many grow on tree limbs but some grow right on the ground. The pineapple is a bromeliad and it grows on the ground.” “I didn’t know pineapples were bromeliads.” “Well, you learn something every day. Let’s go.” The path now passed into a clearing flooded with bright afternoon sunlight. At the far end of the clearing we again found ourselves in the shade, looking down the bank of a noisy stream plunging down the steep mountainside. Spanning the stream was a bridge made of logs sawn in half lengthwise and laid side by side with the flat side up. The bridge was solid but wet and slippery with moss and there was no handrail. We crossed without incident, scrambled up the bank on the other side and found the trail. After crossing the stream, the terrain became steeper than before and our hike became more of a climb. The environment on this side was different too--wetter. There were more ferns, more bromeliads, and most of the rocks were covered with bright green moss. Everything was damp. We were in a cloud forest. Everywhere we looked we saw plants we couldn’t identify. “This place reminds me of the movie ‘Jurassic Park’.” said Phillip. “I’m not surprised. Many of these trees aren’t really trees at all. They’re tree-ferns.” I said, pointing to a nearby example standing about 25 feet tall. “See the shape of the stalk? The stalk is green and covered with fine brown fur like the hair of a monkey, the same as the smaller ferns here on the ground. And look at the leaves. They’re huge but shaped just like other ferns. Tree-ferns have been around longer than trees and are more primitive. They used plants just like these in the movie because they look... well..., Jurassic.” We went to the base of the fern and looked up along the smooth stalk. At the top of a tree-fern, the giant fronds splay out to form a large circle when viewed from below. Each frond has a heavy central stem from which branch smaller stems and from those, still smaller stems, all covered with small, narrow leaves. The result is a symmetry that is one of the most beautiful shapes in nature, like a huge mandala sprinkled with diamonds sparkling as the sun refracts through tiny droplets of moisture on the leaves. The steeper terrain began to be a problem for little Athena. The paths were steeper, sometimes slippery with moisture, and crossed by roots running along the surface of the ground. The flights of steps became more frequent and steeper. Athena was undaunted and resorted to using her hands for stability--sometimes climbing on all-fours. We didn’t slow down and she kept right up with us. I marveled at the versatility of the human body and realized that prehistoric families traveling with children on foot got around better than I’d imagined. We trudged along steadily, too busy huffing and puffing to talk. More and larger granite rocks appeared, mostly covered with moss. Lichens could be seen growing in spots protected by overhanging rock. In places, the path attacked the mountain head-on, climbing steeply up between large boulders. Bromeliads and ferns became larger and more numerous. We crossed several more small streams. Our attention was fully occupied, alternating between looking at the sights around us and watching the path, now narrower, more uneven, and criss-crossed by roots one to two inches thick, breaking the surface like half-buried snakes. We all tripped over them and worried that one of us might twist an ankle. April is especially prone to spraining her ankles and this seemed like a bad place to get stuck. “Hey guys. Wait a minute.” I called, “Come have a look at this”. I squatted down and pointed among some rocks into a dark moss-lined space large enough to hold a basketball. “Do you know what this is?” I asked as I pointed to the clear blob of jelly clinging to the moss. It looked as though a jellyfish had somehow landed here, or like someone had dumped out about a quart of clear, colorless Jell-O. The blob acted like a lens, magnifying the surface of the rock and moss to which it clung. Wide-eyed and in a spooky voice I said, “There are aliens around here. What are we going to do?” “Oh Dad. You’re being silly.” said Athena. “I take it that none of you know what this is. Well, I wouldn’t have known either had I not read about it recently. It’s a slime mold, a very primitive form of life. Pretty weird huh?” “Yeah. We’ll have to come back here again, but right now, we have to get going. It’s almost three o’clock.” said April. “You’re right. Let’s go.” We resumed our trek in earnest. We had no idea where we were or how much progress we had made but the answer soon appeared. The vegetation suddenly changed to ordinary-looking shrubs and trees with mid-afternoon sunshine filtering through. A tunnel-like opening in the bushes provided a narrow view toward the canyon to the east. A small loop of the highway was visible as a tiny track far below. “Gee. We’ve gained a lot of altitude.” I said. “Listen. I think I can hear the waterfall.” said April. Faintly, I could hear something but I wasn’t sure if it was the waterfall or another stream. The trail led on into dense bushes rooted in light tan colored soil and remained fairly level. We were hiking along the ridgeline of the mountain. Our trail dipped down slightly as the vegetation became so dense it crowded the trail. In places, we had to push our way between huge bushes that pulled at our clothes and slapped our faces. The roaring grew steadily louder and began to sound like thunder. It had to be the waterfall. We abruptly found ourselves back among rainforest vegetation and dark brown soil. Another 20 yards and we stopped short on a small platform of rock large enough for about a half-dozen people and surrounded by a rusted steel railing which seemed very out-of-place in this totally natural setting. To one side, a torrent of water roared past, splashing the platform and our feet. April grabbed Athena’s hand. One could kneel and touch the water. The platform trembled slightly from the force of the water thundering by. Cautiously, I moved to the far railing, looked down and gasped. I was looking down the face of the waterfall as it plunged into the depths below me.

The upper part of the waterfall before it plunges hundreds of feet to the rainforest below. “This view is almost too much to take in.” I exclaimed, “I know you don’t like heights, April, but you’re going to have to take a look anyway”. “Do you think it’s safe?” she asked. I replied, “Well, it looks precarious but I think we’re safe. We’re perched on a huge rock outcrop. If it were unstable, the vibration of the water would have knocked it loose long ago”. “Here Phillip, hold on to your sister.” said April as she came to the railing and peered over. Athena stamped her feet. “I wanna see too!” “All right,” I said, “but I’ll have to lift you up”. “Wowww.” Athena said calmly as I locked my arm around her waist and projected her torso out over the railing. Well, I thought to myself, she certainly has no fear of heights! The torrent of water rushing past us was about 20 feet wide and looked about three feet deep. Phillip was on his knees at the other edge of the platform holding his hand in the stiff current as he said, “I’m hungry. Let’s eat some of those snacks we brought”. Leave it to Phillip to know our food inventory. But, a snack sounded good. We had some canned Vienna sausages, bread, and a few more sodas which we enjoyed while admiring the view and snapping photographs. “You know, I completely forgot to look for quetzals.” said April. “I didn’t see any, nor did I see any animal life at all,” I said, “no birds, no animals, no insects, no worms, nothing. I saw a couple of small spider webs covered with droplets of moisture--very pretty--so there must be insects for them to catch, but I saw none.” “Funny. It’s not what I expected”. “Me neither. Did you notice how clean everything is in the cloud forest? No decaying material anywhere. In other forests where we’ve travelled, a fallen tree can lay there for years, rotting. Here, I guess the level of biological activity is so high that when something dies, the material is recycled almost immediately. So, there’s no dead or rotting stuff around. Everything you see is alive and healthy.” “It almost looks manicured. I’d love to do some drawings or paintings of these plants.” said April as she examined another bromeliad with a red flower growing in a little grotto beside the trail. “What time is it?” “You don’t want to know. It’s 3:45. I hope they won’t be too annoyed at us.” I said. April laughed, “What are they going to do? Throw us out?” “They might lock us in.” “I doubt it. We’re probably the only ones here. They know we’re here.” “We haven’t seen a single person since we left the gate.” “Yeah. Ain’t it great?” said April. “All right. Time to go”. The shadows were deepening and the hills to the east had the orange color of late afternoon. I hoped our descent brought no problems. Our packs carried several kinds of cyalume light-sticks but no flashlights. We weren’t prepared for a nighttime hike. It gets cold up there at night and usually rains in the early morning. “We’ve been irresponsible enough for one day.” I remarked. “Yeah, but it was worth it.” said April as she closed the last of our packs. The narrow path led us from the platform to a fork where the way downward branched off. “Shall we take the rest of the trail down or go back the way we came?” asked April as we paused at the fork. “According to the map, as I remember, this new path down is shorter. But, we don’t know what’s ahead of us. We know the path we just came up on.” I said. “I say we go on.” said April. “I agree. We’ve come this far. We might as well finish it”. So, off we went down the new path--switchbacks of inclined trail interrupted by steps, just like the trail we came up on. It seemed like this trail was worse than the trail up because descending is always harder than climbing. I found myself using one hand for stability on some of the steps. Athena held my other hand the whole way down. Fatigue was catching up to her. She stumbled more often. I had to pay close attention to my footing since I was providing stability for both of us and, in our haste, we nearly fell sprawling in a couple of spots. The trees around us I recognized as the same kind we saw in the lower part of the cloud forest, but, for some reason, they were spaced farther apart and the canopy was not solid. Even though it was late afternoon, and we were in deep shadow on the east side of the mountain, there was much more light reaching the ground here than in the forest we passed through on the way up. We had plenty of light to see our way. The ground here was covered with solid vegetation about a foot deep--a lime-green sea of something like ivy with bromeliads poking up here and there. Our descent was rapid as we plunged headlong without stopping to look around. We crossed a few more streams and some beautiful spots but could not afford the time to appreciate them. April and Phillip were getting quite far ahead of Athena and I. We lost sight of them as they trotted back and forth on the switchbacks below us. “Mom! Wait for us!” cried Athena. “You’ll catch up.” a faint voice floated up from far below. Athena pulled my hand as she tried to speed up. “No point in racing, Athena.” I said, “We’ll just go as fast as we can, safely, and we’ll get there when we get there.” “OK. Daddy”. Eventually, we did catch up. Near the bottom, the trail levelled out and ran through a grassy area, straight away from the mountain and toward the highway. April and Phillip were next to a fenced-in corral containing a couple of horses. A half-dozen workers were putting away tools in a shed. They waved at us. One of them traced a small circle in front of him with his forefinger, signaling for us to hurry up, and shouted, “Apurarse! (hurry up)”. We took his advice and continued on to the exit. As we passed the gatekeeper’s shack, he smiled and shook his finger at us accusingly as he came out to lock the gate. It was 5:15. “Well, we made it, but we didn’t see any quetzals.” I said. “I don’t care. It was great.” commented April. Just then, we were startled by a flock of about 30 screeching birds passing low over our heads. They were toucans, coming up from the lower valley on the other side of the highway, headed up the way we had just come. “I’m hungry.” announced Phillip, “I can’t wait to get back to the comedor and eat. I hope the señora still has some tamales left.” Phillip got his wish. We were staying at the Hospedaje del Quetzal, only a couple hundred meters down the road from the entrance to the biotopo and the only place to stay for miles. We were the only guests at the small family-run business so we were treated like family. Over dinner and for the rest of the night, we couldn’t stop talking about the wonderful day we had spent. The owner of the hotel told us that we had a better chance to see quetzals in the trees right outside the comedor than we would in the biotopo! We told him about the flock of toucans and he said that quetzals do the same thing: They fly down, out of the cloud forest, in the morning. They spend the day in the lower valley and return across the highway in the late afternoon. It didn’t matter. We were happy anyway. What we didn’t know was that Mother Nature had a surprise prepared for us. The next morning was bright and sunny and we came down from our room to the comedor for breakfast. It was about nine in the morning. The señora brought us coffee and told us what she had on hand to eat. While waiting for our breakfast, we wandered back outside to stroll among the trees and sip our coffee. April was still thinking about what we’d been told the night before about quetzals and was looking up into the huge trees overhead.

One of the trees where quetzals were perched. The trees are taller than they appear in the photo. The branches are loaded with air plants and bromeliads. “Hey!” she called to me, “Your eyes are better than mine. Tell me if you see something up there near the top of that tree.” I looked where I thought April was pointing and scanned every branch near the top. There, in a shadow, was a bird. It was in shadow and looked reddish on the bottom but that was enough for me to yell, “Phillip! Run up to the room and grab both pairs of binoculars, quick!” I tossed the key to him and he took off on his long legs like a bullet. Our room was in a small cabana about a hundred yards up the hill, so it took longer than I would have liked for him to return. April and I tore the 7x50 field glasses out of their cases and looked. “It has to be a quetzal. He’s directly overhead, so all I can see is that he has a blood red breast and belly.” I said. I moved farther and farther from the tree to get a better angle on him but the tree was old and very tall. The trees were so dense, I couldn’t improve the view without it being blocked by other trees. Suddenly, April announced, “I’ve found another one.” “Where?” “Over there.” she said, pointing to the top of another tall pine about 400 feet away, on the hill behind the comedor. I soon found it. “Yeah!” I shouted, “That’s a quetzal for sure. Almost a perfect side view, just like the photos I’ve seen. O.K. Now that I’ve seen this one, I’m certain the one overhead is a quetzal too. Well, we finally got to see not one but two!” April started laughing and said, “I’ve found another one.” “You’re kidding. Where?” “Right there, in the same tree, down and to the left”. I looked and there it was. I couldn’t believe our good fortune. “I wish I could see one fly. They just sit there like statues.” I said. “No. I saw the last one because it moved from one branch to another”. “There’s no point in taking a picture. I’d need a tripod and a 400 millimeter lens.” I lamented. “You’re not going to believe this.” said April, “I’ve found another one.” “This is crazy.” I yelled, “Four quetzals? Where is it?” By now, our breakfast was ready and the señora came out to see what the ruckus was about. All our yelling and pointing made it pretty obvious, I suppose, and she called her husband over. So, there we were, all six of us pointing at the trees like a bunch of kids, when a pair of policemen drove in from the highway for their customary morning coffee break. Naturally, they were curious and joined us. One was a middle-aged sergeant with the pot belly that seems to go along with his rank; His partner was a young recruit. Neither of them had ever seen a live quetzal! I expressed my astonishment that this was so, since their beat was this highway that ran through the biotopo, but I snapped my mouth shut lest I offend. To mend any hurt feelings, I handed over my binoculars to the sergeant and pointed at one of the quetzals. But he just looked at the binoculars in his hands, then back at me, and back at the binoculars. I concealed my surprise as I realized he had never handled a pair of binoculars before. Charging past his discomfort, I showed him how to set the focus and diopter, borrowed April’s binoculars, and showed his partner. The cops were thrilled. An old Q’ek’chi Mayan Indian man had quietly joined us, and was listening to our chatter and looking up at the birds. He came over to me and said in broken Spanish, “You are very fortunate”. “I am? How so?” He explained, “There are four people in your group. There are four quetzals in the trees. It is a rare blessing of good luck.” |